Today is the 30th anniversary of Apple Computer, Inc., and to mark the occasion I cranked up my old Apple II -- more precisely, my Apple IIc. A successor to the original Apple II computer, which was released in 1977, the IIc came out in 1984. It cost $1,295 and came with a single 5 1/4" floppy disk drive, 128 kilobytes of RAM, and a cable that connected the computer to a television. A color monitor was $200 extra.

The IIc was meant to extend the life of the venerable Apple II technology, which had made the company's fortune. But there was something new with the IIc: unlike the original Apple II, the IIc came in a case that was sealed at the factory, and owners could not easily open it to install extra memory, expansion cards and so forth. The openness of the original Apple II's design was partly what made it so popular (especially with hobbyists and tinkerers), and IBM incorporated a similar openness into the design of its original PC -- which is why, to this day, it is still easy to pop open the case of just about any desktop Windows computer and install network cards, sound cards and so forth.

My recollection is that Apple cofounder Steve Jobs had always been uncomfortable with the openness of the Apple II. That is why Apple's Macintosh computers came in factory-sealed cases from the very beginning -- the original Mac also came out in 1984 -- and why, I suspect, the IIc did as well.

My IIc used to belong to my great aunt Edith, who I believe picked it up at a church bazaar. She gave it to my family, and it sat in a Nashville attic for about 15 years before I brought it to Wisconsin. If you know what Nashville attics are like in summer, you'll be as surprised as I was to learn that the old contraption still works just fine. That speaks well for Apple engineering.

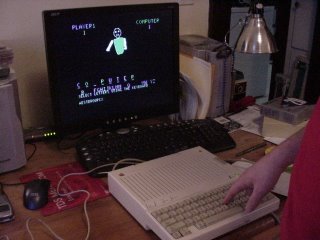

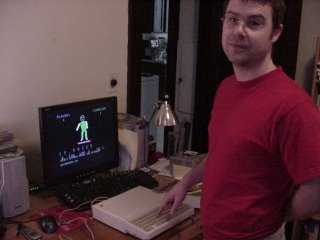

Here are some pictures. I'm not sure what compels me to hook this thing up every now and then, but as Ereck demonstrates, it remains good for playing hangman.